To be a productive scientist these days, you sort of need to have some interaction with code - whether that’s a one-off Rmarkdown notebook following an RNAseq tutorial or a handful of scripts copied from a colleague to run stuff on the cluster. Many “wetlab” (experimental) scientists, at least those I know, are intimidated or overwhelmed about learning “drylab” (computational) skills. So I’m putting together a series of tutorials - “Drylab Skills for Wetlab Scientists”1. This is the first one!2

You git what?

So you’re dealing with some code - whatever its origin. Don’t put it in a word file in your one drive or google drive. Don’t keep a bunch of scripts in a folder called scripts/ on your desktop that you keep copy/pasting to other locations to use and modify. Don’t just ignore it and hope it will go away. You should really be using git.

You’ve probably heard of git or at least github (they’re different!). Maybe you’ve followed a forum/stack overflow/bluesky post down a rabbit hole and ended at a github readme file, or had a reviewer ask for a link to your code. If you’re reading this, you probably also know that you really should be using git, but don’t quite know what it is, why it’s useful, or how to fit it into your workflow.

That’s OK! We’ll go through all of that. But you also may not be convinced that all of this is worth it - the unfortunately reality is that the usefulness is hard to see until you use it a bunch, and it can be hard to practice or be diligent about using it if you don’t see the utility.

But trust me. And if you don’t trust me (that’s fine, we just met!), trust the fact that basically anyone developing software at any level uses git. And there used to be many kinds of software that did a similar thing, and git has eaten them all.

What is git?

In technical terms, git is a “version control system” (VCS) - specifically, a “distributed version control system” (DVCS). VCS means that it manages files as they change, and “distributed” because every machine that has the files can keep track of versions themselves - this is in contrast to older VCS where a central computer managed the versions and one had to “check out” files to make changes (often only one person could edit at a time).

But more colloquially, git gives your computer’s directories superpowers. Superpowers to fix your mistakes, sure, but also giving you the freedom to mess around with freedom to know that you can always get back to where you were. And the freedom to collaborating without worrying that you will screw up your collaborators’ code.

Have you ever encountered one of the following problems?

You had a working version of some code to plot a figure, but decided to make some tweaks to the design. In the middle of these tweaks that aren’t finished, your PI asks for that figure RIGHT NOW, but the code won’t run in its current state.

You are writing letters of recommendation for a student that’s applying to a bajillion graduate programs, and you’d like to change the greeting for each one (eg “To the graduate admissions committee of University of Awesome,”…). You end up with a bajillion word documents in a folder that you’ve meticulously edited, but then realize there’s a typo in the 3rd sentence.

Your colleague shared a little bash script to do something useful on the cluster. You want to make a few tweaks (maybe with the help of ChatGPT or claude), but want to hang onto the original. as you’re trying things, you end up with a directory containing

neat-script-orig.sh,neat-script-mod1.sh,neat-script-mod1-fix.shetc.

Git can help will all of these, and I’ll show you how.

What is github?

Github is a “code forge,” which I like to describe as a social media layer over git. As an analogy - if git is like an address book and email protocol, github is like facebook - it adds a bunch of features on top of the open protocol, but requires being signed in.

There are lots of other forges like gitlab, gitea, and codeberg, but github has been around a long time, and is probably the most popular (though it was bought by Microsoft years ago and is steadily being enshitified).

Intro to git part 1 - Understanding the model

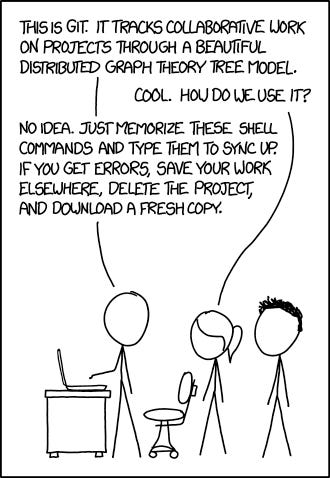

This first video is just trying to help you understand the overall model - the beautiful distributed graph theory tree described in the xkcd cartoon.3

If you have any questions or any skills you’d like a video on, let me know in the comments!

More resources

What is git and github? - a description in plain english

Learn git branching - a series of interactive tutorials

Learn git, from gitkraken

Glossary

These terms will come up frequently when using git and github,

and are included here as a reference.

A more complete list can be found here

repo (short for repository) - a folder with git super powers

stage - a new file or a change to an existing file that will be included in the next commit (when you

git add $FILE, then$FILEis now staged)add- include the file or file change in the next commitcommit(verb) - register staged changes to the version historycommit (noun) - the record of changes from the previous version

remote - a location different from your current system that the repo also lives. This is often on something like github or gitlab, but could just be another one of your computers that you can connect to. It could even be a different directory on the same computer!

push- move commits from your local repo to a remote. If you’re not paying attention, this can lead to merge conflicts (which is OK!gitis built to handle this).pull- move commits from a remote to your local repo. If you’re not paying attention, this can lead to merge conflicts.branch - an alternate history of commits

merge - join the version history of two branches

merge conflict - when merging branches that each have changes to the same line(s), and user input is required to decide which version to include

origin - the default name for a remote

main/master - typical names for the primary branch of a repo

PR (pull request) - when using

gitsocial networks (eg github), an interface to comment on a branch that could be merged into themainbranch. On gitlab and some other forges, this is called a “merge request” (MR) insteadissue - when using

gitsocial networks like (eg github), an interface to discuss problems, potential features, or other information about a repo.

Well, the first planned post - I made this for folks struggling with the new NIH biosketches made on ScienCV

This needs a pithier name - “Moist lab skills?” “The Damp Lab”? “Towel skills?” If you’ve got ideas, let me know!

The alt text for the comic says “If that doesn’t fix it, git.txt contains the phone number of a friend of mine who understands git. Just wait through a few minutes of ‘It’s really pretty simple, just think of branches as…’ and eventually you’ll learn the commands that will fix everything.” Feel free to put my contact info in your git.txt 😅